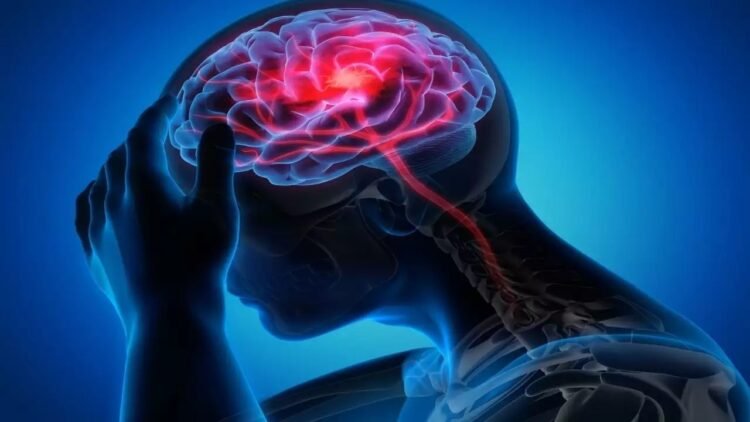

FREDERICTON — Melissa Hawkes first began feeling unwell during a visit to a friend’s home in March 2021. All she remembers before blacking out is heading to the bathroom. When she came to, she was lying on the floor, surrounded by her friends and fiancée, all looking deeply concerned.

“They told me, ‘You had a seizure,’” said Hawkes, 27, who was living in Moncton, N.B., at the time. “I was meeting these people for the first time. It was so embarrassing.”

What started as mild symptoms, like intense fatigue and nausea, has since developed into a serious condition. Hawkes experienced a second seizure in 2023, has nerve damage in her wrist, and suffers from necrotizing gingivitis — a painful gum infection.

Hawkes is one of nearly 400 New Brunswick residents dealing with a “neurological syndrome of unknown cause.” This mysterious brain disease appears to predominantly affect people in the Acadian Peninsula and Moncton areas. Her fiancée, Sarah Nesbitt, has also been affected.

In February 2022, the province’s Health Department under the Progressive Conservatives concluded that there was no evidence of a cluster of cases. However, patients experiencing symptoms such as memory loss, balance problems, behavioral changes, muscle spasms, and severe pain disagreed, urging the government to continue its investigation. The Liberal Party campaigned on reopening the probe, and after their election victory in October, the new government has resumed the inquiry.

A Growing Concern

Health Minister John Dornan noted that much has changed since the initial investigation. Back in 2022, fewer than 50 patients were reported. Now, there are over 400.

“We haven’t been able to easily pinpoint a common cause or treatment, which makes this a significant challenge,” said Dornan. His mandate from Premier Susan Holt includes conducting a scientific review into the syndrome.

Dr. Alier Marrero, the neurologist who initially investigated the cases in 2020, has shared his files with both provincial and federal health teams, including the Public Health Agency of Canada. Marrero was unavailable for comment.

Dornan explained, “It’s a new phenomenon. Whether it’s a disease, syndrome, or something else entirely, our first priority is understanding it.”

Federal Health Minister Mark Holland praised the collaboration between provincial and federal health agencies, saying, “We’re working to gather data and evidence to understand what’s happening and determine the best course of action.”

Environmental Factors Under Scrutiny

Hawkes and other patients have called on the government to test for environmental toxins, including the herbicide glyphosate. In January 2023, Marrero urged health authorities to investigate possible links between the symptoms and the chemical.

Dornan stated the investigation would progress step by step. “We need to identify a common denominator first. Environmental factors are part of the testing already conducted, and we’ll evaluate all available data.”

Hope Amid Uncertainty

Hawkes, who is under Marrero’s care, described the reopening of the investigation as a “good first step.”

Still, she expressed frustration over the slow progress. “People have died. I’m absolutely terrified,” she said.

Her fiancée, Nesbitt, 41, noted that some of her symptoms have improved five years after they began. Since moving to Canaan Station, N.B., and making lifestyle and dietary changes, Nesbitt has seen positive changes. She also plays video games to enhance hand-eye coordination.

“There are still things that are getting worse, but many symptoms have eased,” she said. While seizures and tremors persist, they occur less frequently. She can now stand for longer periods, and nerve tingling on one side of her body has reduced. “A lot has improved. I’m just not fully better yet.”

A Long Road Ahead

The journey has been difficult, especially after the government declared the matter closed in 2022.

“They are listening now,” Nesbitt said of health officials. “But what we need to see next is action.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published on Jan. 19, 2025.

English

English